By Klaus W. Larres, University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

U.S. President Donald Trump took a tough line in his address to the nation Jan. 8 in response to the Iranian airstrikes on two U.S. bases in Iraq.

Trump announced that he would impose more sanctions on Iran. He said he believed that Iran would not resort to further aggressive action for the time being. He blamed his predecessor President Barack Obama for having concluded the 2015 nuclear deal with Iran and for having dealt too gently with the country.

Trump also extolled U.S. military power, which he claimed had been much improved during his presidency. He said he would not hesitate to make use of this awesome technology, if necessary.

“Our missiles are big and powerful and accurate … and lethal,” he said.

Trump also announced that the U.S. did not wish to use these powerful weapons if Iran started to behave in a more reasonable way in the region.

But Trump’s address wasn’t entirely directed at audiences in the United States and Iran.

Allies’ muted response

Trump was also speaking to America’s European allies.

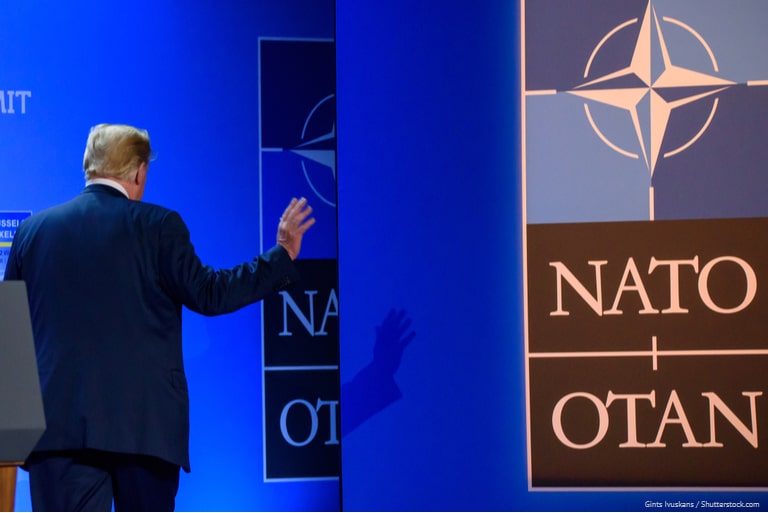

As an international relations scholar and practitioner of diplomacy, I don’t think many of them were pleased to hear Trump’s announcement that he would ask NATO – the 29-member North Atlantic Treaty Organization – to “get more involved in the Middle East.”

In particular, Trump encouraged NATO members the U.K., France and Germany – and also China and Russia – to change their policy and finally give up on the 2015 nuclear agreement negotiated by the Obama administration, but abandoned by Trump.

Reactions in Berlin and London have been muted, though so far none of the NATO allies has dared to openly criticize the president’s speech. Perhaps that is because Trump’s touchiness about any criticism is well-known.

Trump’s suggestion that the NATO countries get more involved than they already are in the Middle East flies in the face of his longtime disparagement of the alliance.

Fighting the Islamic State

German troops have been in Iraq since late 2015 to train Iraqi security forces in the fight against the Islamic State group. These troops are not meant to fight in the region.

After the killing of top Iranian Gen. Qassim Soleimani, the Germans withdrew to Kuwait some of their 120 troops stationed in Iraq. The Germans also announced that they may shift their remaining forces to Jordan or other safer areas.

Germany believes that saving the nuclear deal is still the only realistic way to engage with Iran and prevent Iran from restarting its nuclear weapons program.

Trump’s speech was also most likely viewed skeptically in London.

The British have 1,400 troops in Iraq and Syria for both training purposes and for fighting the Islamic State. They are uneasy about the increased danger to their military personnel since Trump’s airstrike on Soleimani which was not coordinated with London or NATO headquarters.

London also believes that the 2015 nuclear deal ought to be given another chance. Re-engagement with Iran rather than pursuing a war path is also the conviction in the U.K.. In fact this continues to be the shared view of diplomats from the U.K., Germany, France, China and Russia.

Despite his calls for U.S. allies to join ranks in the Middle East, President Trump remains the odd one out.

Klaus W. Larres is Richard M. Krasno Distinguished Professor and Adjunct Professor of the Curriculum in Peace, War and Defense at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill

Note: The views expressed in this article are the author/s, and not the position of Intellectual Dose, or iDose (its online publication). This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.