By W. Joseph Campbell, Professor of Communication Studies, American University

Election polling is facing yet another reckoning following its uneven-at-best performance in this year’s voting.

Although the outcome in the 2020 presidential race remained uncertain the next day, it was evident that polls faltered, overall, in providing Americans with clear indications as to how the election would turn out.

And that misstep promises to resonate through the field of survey research, which was battered four years ago when Donald Trump carried states such as Wisconsin, Michigan and Pennsylvania, where polls indicated he had almost no chance of winning. Prominent, poll-based statistical forecasts also went off-target in 2016.

Those failings deepened the embarrassment for a field that has suffered through – but has survived – a variety of lapses and surprises since the mid-1930s. Many of those flubs and failings are described in my latest book, “Lost in a Gallup: Polling Failure in U.S. Presidential Elections.”

Criticism was intense in some on the day after the election. Politico’s widely followed “Playbook” newsletter was notably scathing. “The polling industry is a wreck,” it declared, “and should be blown up.”

Many surprises

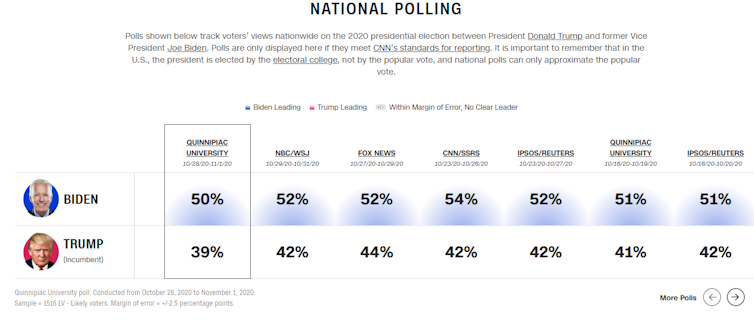

While that assessment seems extreme, especially given polling’s resiliency over the decades, the poll-driven expectation that former Vice President Joe Biden would lead Democrats in a sweeping “blue wave” went unfulfilled.

Biden’s overall polling lead, as compiled by RealClearPolitics.com, stood at 7.2 percentage points on the morning of Election Day. A little more than 24 hours later, his lead in the national popular vote was almost 3 percentage points.

Pollsters often seek comfort, and protection, from critics in asserting that pre-election surveys are not predictions. But the nearer they are to the election, the more reliable polls ought to be. And a number of individual pre-election polls were embarrassingly wide of the mark.

A notable example was the final Washington Post/ABC News poll in Wisconsin, released last week, which gave Biden a stunning 17-point lead. The outcome there was a Biden victory of less than one percentage point, a margin nowhere close to 17 points.

Indeed, the polling surprises were many and included Senate races such as those in Maine, where Republican Susan Collins appears to have fended off a well-financed challenger to win a fifth term, and South Carolina, where Republican Lindsey Graham rather easily won reelection despite polls that indicated a much closer race. Graham declared after his victory became clear, “To all the pollsters out there, you have no idea what you’re doing.”

It appears that Republicans will keep control of the U.S. Senate despite expectations, fueled by polls, that control of the upper house was likely to flip to the Democrats.

Polling problems not new

The 2020 election may represent another chapter in the controversies that have periodically surrounded election polls since George Gallup, Elmo Roper and Archibald Crossley initiated their sample surveys during the 1936 presidential campaign. The most dramatic polling failure in U.S. presidential elections came in 1948, when President Harry S. Truman defied the pollsters, the pundits and the press to win reelection over the heavily favored Republican nominee, Thomas E. Dewey.

The surprise this year is not remotely akin to the epic polling failure of 1948. But it is striking how polling missteps are so varied, and almost never the same – much as Leo Tolstoy said of unhappy families: each “is unhappy in its own way.”

Factors that gave rise to this year’s embarrassment may not be clear for weeks or months, but it is no secret that election polling has been confronted with several challenges difficult to resolve. Among them is the declining response rates to telephone surveys conducted by operators using random dialing techniques.

That technique used to be considered the gold standard of survey research. But response rates to telephone-based polls have been in decline for years, forcing polling organizations to look to, and experiment with, other sampling methods, including internet-based techniques. But none of them has emerged as polling’s new gold standard.

One of polling’s most notable innovators was Warren Mitofsky, who years ago reminded his counterparts that there’s “a lot of room for humility in polling. Every time you get cocky, you lose.”

Mitofsky died in 2006. His counsel rings true today.

Dr. W. Joseph Campbell is a Professor in the School of Communication’s Communication Studies program at American University

Note: The views expressed in this article are the author’s, and not the position of Intellectual Dose, or iDose (its online publication). This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license.