By Duncan Green, Strategic Adviser Oxfam and Professor-in-Practice LSE’s Department of International Development

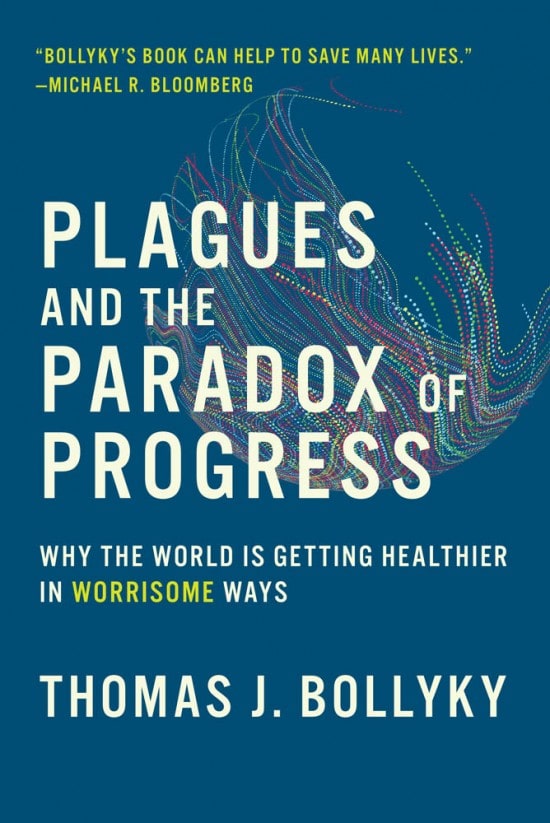

If you want to step back and think more broadly about Coronavirus, the Universe and Everything, you could do worse than start with Plagues and the Paradox of Progress, by Thomas J. Bollyky, which combines a ‘germ’s eye view’ of human history with some powerful reflections on the challenges that face us over the coming decades.

First, the history. The book has that rare quality of making you look at familiar events and issues in a new and unfamiliar light – not least, seeing human history as an ancestral battle between germs and people.

When people moved from hunter gathering to agriculture, the germs celebrated – people living closer together means contagion booms. The rise of the cities delighted the microbes even more. For centuries cities were stews of infection, where life expectancy lagged way behind the supposedly ‘backward’ countryside.

Fighting the germs spawned many modern institutions – nation states, municipal governments – and more recently, global efforts against epidemics helped forge forms of control and cooperation (quarantine, vaccination, housing reforms, sanitation and safe water) that then became the blueprint for working together on other problems. Charles Tilly said ‘war made the state and the state made war’, but in this reading, it was the germs.

Bollyky provides a fascinating historical typology of disease, with a chapter on the human response to each. He distinguishes between diseases of conquest and colony (smallpox and malaria); diseases of childhood (measles and other respiratory conditions); diseases of settlement (tuberculosis and cholera); and diseases of place (meningitis and other neglected tropical diseases).

Cities were synonymous with squalor and disease, but around the year 1650, there was a turning point. Conditions began to improve, first in European cities, before spreading to the US, Australia and elsewhere. Urbanisation took off. The gains preceded the discovery of new treatments – state institutions and public health systems delivered sanitation, reduced overcrowding, etc, long before the vaccines arrived. Medical technology followed, completing the job. Despite setbacks such as new diseases and epidemics, people started to win the battle against germs. Fast forward to this century and fatal infection in rich countries has been a rarity – we have generally worried about other health issues.

But what of poor countries? Bollyky argues that there has been a reversal of the historical order of events: medical technology has outpaced institutional development, with profound implications:

The last two decades have brought dramatic reductions in endemic infectious disease and child mortality, but not the improvements in health-care systems, responsive governance and employment opportunities that accompanies those changes in wealthier nations in the past.

The citizens of Niger are poorer now (in terms of GDP per capita) than they were 25 years ago, yet a person born in Niger today can expect to live fourteen years longer than someone born in the country in 1990. A combination of aid and medical technology has worked wonders in the poorest countries of the world. One consequence has been the recent phenomenon of megacities in the Global South – previously, all the large conurbations were in the rich world.

This is all great news obviously – millions of deaths averted, lifetimes of human suffering avoided. What Bollyky worries about is what awaits the survivors:

Rapid population growth, unprecedented urbanization, and an increase in the share of young adults are straining the capacity of governments and ecosystems while spurring migration, instability and the risk of pandemic diseases and chronic ailments […] It is not hard to envision that the next two decades in lower-income nations may be more violent and conflict-filled than the last, reversing some of the great progress that has recently occurred.

To prevent this fate, Bollyky has some fairly cursory advice for governments: namely, invest in urban infrastructure, education and healthcare. His real target is the aid sector.

He traces health aid’s roots to colonial and military campaigns, which have left a legacy of vertical programmes – ‘crusades’ against one or other disease along the lines of the iconic eradication of smallpox, and then turbocharged by the response to HIV/AIDS. These came at the expense of attention to institutions – health systems and other infrastructure. He contrasts this approach to the more horizontal structures created by China, Costa Rica, Sri Lanka and others, using home-grown low-cost strategies like barefoot doctors rather than pharmaceutical magic bullets.

Plagues and the Paradox of Progress suggests three changes of direction for the aid sector:

- Recast global aid programmes from disease-focused goals to more outcome-oriented measures for improving health.

- Fund data collection and research that advocates and activists need to advance locally inspired change and support local reformers in pressing their governments for better policies.

- Politicians in the wealthy nations must come to terms with the inconsistencies of their policies on climate change, global health, trade and immigration.

Oh, and the book is beautifully written, packed with great one-liners and historical anecdotes. Perfect reading during lockdown.

Duncan Green is a strategic adviser for Oxfam GB. He is also a Professor-in-Practice in LSE’s Department of International Development

Note: The views expressed in this article are the author/s, and not the position of Intellectual Dose, or iDose (its online publication). This article is republished from the LSE Review of Books under a Creative Commons license.