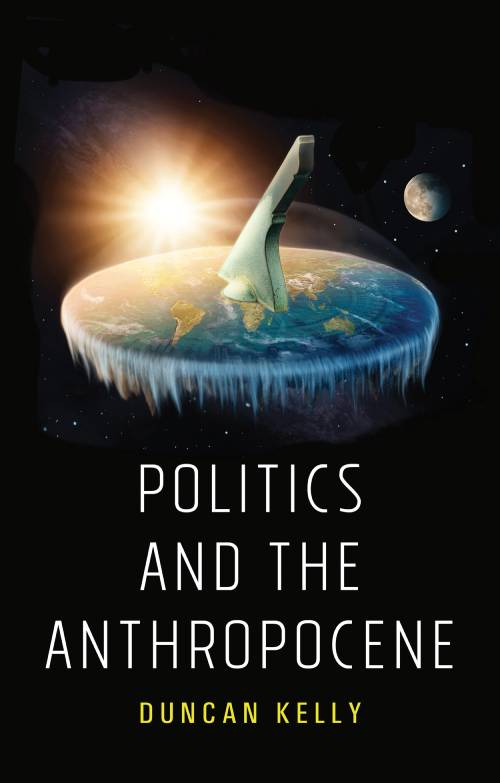

In his new book Politics and the Anthropocene (Polity), Duncan Kelly, Professor of Political Thought and Intellectual History at the University of Cambridge, considers how this new geological era could shape our future by engaging with the recent past of political thought and the potential for democratic politics to negotiate this challenge. In this interview he speaks to Robert McLachlan, Distinguished Professor in the School of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, who writes on climate and the global ecological crisis at planetaryecology.org.

Politics and the Anthropocene: Interview with author Duncan Kelly on ‘a puzzle, a problem, a dilemma’

Robert McLachlan: Today we seem to be seeing the convergence of several factors: the ecological crisis; an apparent change in democracy such as the decline of the traditional political parties; the rise of social media; and the emergence of ‘fake news’. Is their simultaneous emergence a coincidence? They seem to be related.

Duncan Kelly: They are related in some way. The climate crisis, and our awareness of it, is connected to a deep-seated worry about the future of democracy and its ability to cope with crises that affect the lived environment. Also, the post-truth phenomenon is much more easily seen through the prism of the climate catastrophe, because it’s such an obvious space in which actors can disagree. The disagreements can be curated in particular spaces, especially online ones which allow people to filter their viewpoints and find out what they think they want to hear, and then see more of what they think they want to know. There must be connections between those things, although it’s difficult to say if one causes the other.

Some people argue that because democratic politics is so (relatively speaking) new, the fact that it’s in a slump or crisis is only what we should have expected. All political regimes rise and fall. Democracy as we know it, for most people, is only 100 years old. And even then, it was hardly equality for everyone. It still doesn’t signify for most people in most places anything beyond the most rudimentary equality, where everyone gets a vote. We’ve become accustomed to democracy over several generations, but there’s no reason to think it will last forever.

RM: So if we believe in the future of democracy, we need to be constantly reminding people of what it is and its value.

DK: Absolutely. But so many clever and interesting people over the last 70 years have argued that the best thing about democracy is that it is so minimal that you can disaggregate the value from the process. If all you want is a fairly thin account of democracy as a procedure –everyone has citizenship, everyone has the right to vote, democracy is just about the competition for votes between the politicians and the rest of us, the politicians get on and do what they want and leave us alone to do what we want – then that’s the best you can have. But that suggests that democracy itself doesn’t have any intrinsic value; it’s just a process.

RM: In climate change circles, it’s discussed whether this global-scale ecological problem is a fundamental difficulty for democracy. Perhaps it’s only a difficulty for this very thin democracy?

DK: I think so. Because we so readily think of democracy as bound up with nations and territories and states that have their own interests and populations which are supposed to come first, it’s difficult to see the possibility of democracy as a procedure that can unify a set of interests between states. This is why international agreements are so very difficult to achieve. That’s before you even get down into the detail of what people are trying to discuss, like treaties and regulations. International cooperation is massively difficult.

RM: It’s difficult, and we don’t have many positive examples.

DK: That’s true. One of the things I tried to do in The Politics of the Anthropocene is to say that even the sorts of examples that we have of large-scale international management and cooperation, from the League of Nations after the First World War through to the United Nations and the Sustainable Development Goals, all come packaged in ways that have their inequalities baked into them from the outset. Assumptions about civilisation and hierarchies, racial and economic exclusions, are so deeply entrenched in the mindsets of the people who were involved with them that they were bound to run into the limits of their own imagination quite quickly.

RM: You nonetheless write that the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) 1.5ºC report is a ‘radical political document’.

DK: I think it is! Their reports, both 1.5ºC and the more recent one on land use, have become increasingly radical, in tone and in message. The language through which the radicalism is expressed is often very, very flat – and has to be, because it’s not supposed to be an overtly political document. However, that slogan, ‘1.5 to stay alive’, was incredibly radical. It captured something of the zeitgeist. People do recognise that temperature is a very obvious manifestation of climate change, even if you read David Wallace-Wells’s recent popular book, just laying out in narrative fashion what is already happening and what is inescapably going to happen. It won’t take much warming for humans to become unable to survive in certain climates. So where should the action be, politically, in response to this document? It does seem to be another instance where an environmental conclusion becomes a motivation for individuals: you think ‘what can I do to change my behaviour?’ Though whether it opens up the possibility for large-scale political or corporate change is a really difficult question.

RM: You’re strongly opposed to fatalism, of both the optimistic kind (‘technology and markets will save us’) and the pessimistic (‘we’re doomed, why bother trying?’). That suggests that fatalism has to be overturned first, before we can make progress.

DK: I think so. Although it sounds glib to say so, often one needs a crisis to motivate political change. Yet it’s a very difficult gambit, a tragic dilemma. If there is a climate crisis then that might motivate people to think differently, but it could also make action impossible. In politics we need to keep options open. That’s one thing that mainstream politicians are very well aware of. But their reason for keeping options open is to delay decisions, because decisions constrain their capacity to manoeuvre. Looked at the other way around, what people who think about politics want to ensure is that there’s a way of seeing the world differently from just the constraints that are taken as given: namely, the idea that there’s no possible alternative to the current system.

Image Credit: (Sam Saunders CC BY SA 2.0)

Image Credit: (Sam Saunders CC BY SA 2.0)

RM: Is that something that is provided by activists like Extinction Rebellion? Many people are inspired by them, but some are alarmed that it looks undemocratic and out of control.

DK: I can see both sides! When people feel strongly enough to march, mainstream politicians have to take them seriously. And people are going to think, ‘Is it really that bad? Have I misunderstood?’ But there could be many things that people might want to think about on how they might engage with climate change. Not everyone is going to want to stand in the streets. But they can help raise awareness, and in doing so, they are able to help us think about how we might change the narrative and the vision. And that’s crucial.

RM: You write about the limits to growth. It’s striking that the whole idea of limits to growth has been studied for several hundred years. We appear now to be bumping right up against those limits, and yet there’s still no consensus on whether economic growth can or should continue forever.

DK: And it’s very difficult for politicians to get out of this mindset, too. Economic growth helps fund them. It supports the regime that has been, historically speaking, successful. The idea of perpetual growth is the kind of hope or panacea that allows you to get to the point of Donald Trump or Elon Musk. It allows you to say: ‘Look, as a species we’ve come up against these sorts of crises in the past, and economic advancement or necessity has fuelled technological innovation which has solved particular problems.’ To me, that’s precisely one of those ‘optimistic fatalist’ arguments that we should be worried about. Because at some point one of these crises is going to be so big and so difficult and so intractable, that that might be the end. But that’s also a difficult position to think about politically, because if you think it’s the end times, then what’s the point in doing anything?

RM: There’s another scenario which is almost as bad, in which you do have continued economic growth and continued ecological decline, and the debate doesn’t move forward.

DK: Yes, it’s a very difficult thought for most people to get their head around. In people’s everyday lives, however they make their living, they’re often told that (in this individualistic society) if you work hard, you’ll do well, and if you do well, you’ll make money, and you make money because the system is geared towards growing and expanding in perpetuity. This is a system of political and social order whereby people assume that what they do matters only for them, and that they are the fundamental unit of analysis: societies that people for shorthand call ‘neoliberal’. Even since the Second World War, you can see that along with the ideology of economic growth, there’s been an increasingly rapid series of ecological crises. There has to be some sense in which we might wonder about the balance between the environment we inhabit and our actions within it and our effects on other species. Many economists and political theorists have, in fact, been thinking about this for a very long time.

RM: So do we need to defeat neoliberalism before we can solve ecological problems? Or is neoliberalism more of a superficial phenomenon, a symptom?

DK: It’s more a symptom. Values will change. The narratives that we tell about the values that we share, or that we’d like to share, will change. That’s just the ebb and flow of human societies. Neoliberalism is not eternal, just like the so-called Thirty Glorious Years of Keynesian economic growth was not eternal. One of the lessons of politics, if there is one, is that nothing lasts forever. So the spaces are always open. The question is, what triggers a shift in the narrative? Is it necessarily a crisis, an explicit recognition of failure? Or can people change the narrative because they have better arguments? And the capacity to mobilise them! Plenty of people have better ideas about economics than boilerplate neoliberal editorials in certain newspapers, but no capacity to bring them to bear on mainstream party politics: that’s a real disconnect.

But I do think that it’s possible for politicians to change the game both from within, and for the game to be changed from without. In the Scottish independence vote, 16-year-olds were allowed to vote. In the UK we see different sorts of cleavages and interests, depending on age, education and geography – all within a very disparate and disunited UK. You could easily see a radical shift if the voting age were lowered to sixteen. Some people think it should go lower; some people think it’s ludicrous to change it. If there is going to be transformation, it’s going to come mostly from the younger generation.

Image Credit: (Gabriel Civita Ramirez CC BY SA 2.0)

Image Credit: (Gabriel Civita Ramirez CC BY SA 2.0)

RM: A related question, ‘What do we actually owe the future?’, also never seems to arrive at a consensus view.

DK: This debate has been going on for at least 70 years. The connections between science, politics, policy and internationalism in debates about intergenerational justice are incredibly difficult. Why I began and ended my book with a discussion of what the Anthropocene opens up in thinking about competing timeframes for understanding politics and history now is that the issue of intergenerational justice strikes most of us as difficult to think about. It’s easy to say, ‘I’d like the world to be better for my children.’ But what does that mean? How do we think about the timeframe involved in that? Most parents hope to see their children live to adulthood and begin to flourish. But at least there’s an overlap of generations. You see your children and perhaps your grandchildren. But what does justice require into the very, very long future?

The best work in this area in the past 50 years has butted up against a problem of timing. Can we really imagine the mindsets of other humans hundreds of years after our deaths? Or how our actions will be judged by them? And what we owe to these distant others? There’s more here than just the way we know our actions have an impact on their future environment. To go back a step: thinking about intergenerational justice going forward might require us to think more about it looking backward. How did we get here? That’s why I think that historians of political and economic ideas might have more to say about a puzzle, a problem, a dilemma like the Anthropocene.

RM: The dominant strand in climate change responses is all about technology, legal remedies, economics and so on. My impression is that you think that’s not going to be enough.

DK: It may be – it may be that’s just what we do, we muddle through. That’s democracy’s history! It may have some grand origin moments, and crises; it may ebb and flow. It might not survive into the future, and that might be no bad thing. There may be better or different ways of doing politics.

But although I see a need to challenge the perspective through which we do our politics, it may be that doesn’t happen; but our politics will nonetheless have to cope with what the climate throws at it, and what that means for massive displacement of people and resources, when places become uninhabitable. When populations do move, when resources do shift between the Global North and the Global South – if we still call them that – then politics will have to deal with it. This goes back to whether or not it’s crisis that motivates political change, or whether political change can come without the need for war, revolution or, in this case, climate epoch-alypse.

Although I don’t think there are any obvious answers as to what we should do in the face of massive climate displacement and a challenge like the Anthropocene, we need to see politics as a problem space that always has to be kept open, that avoids the thought of an inbuilt teleology or fatalism or the belief that it only ever works within the contours and constraints of an ideological system that says, ‘This is the only way. There is no alternative.’

Much of the most interesting work, in theory and in practice, in the history of political and economic ideas over the past hundred years and more has been precisely geared towards teaching us that politics is not just about process, it’s not just about constraint, it’s not just about an ideology. It’s about seeing a shifting, human predicament, moving forward in time and space, and seeing people’s ways of dealing with values and conflicts over resources. Putting them in historical perspective and saying: ‘Look, there are a whole series of different ways we could do this. Some of them are less stupid than others. Maybe we should try them?’ And that’s it. That’s all I’m in any position to say.

Duncan Kelly is Professor of Political Thought and Intellectual History in the Department of Politics and International Studies, University of Cambridge, and a Fellow of Jesus College, Cambridge. He is a co-editor of the journal Modern Intellectual History, and has written broadly on the history of modern political ideas. This interview touches on themes from his most recent book, Politics and the Anthropocene (Polity Press, 2019), and he is currently working on an intellectual history of the First World War.

Robert McLachlan studied mathematics at the University of Canterbury and Caltech, focusing on scientific computing, and is now Distinguished Professor in the School of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand. He writes on climate and the global ecological crisis at planetaryecology.org. In a recent article for Scientific American Blogs, he argued that the framing of anthropogenic climate change as a global tragedy of the commons was slow to be discovered, slow to be appreciated and has yet to achieve widespread popular recognition.

Note: The views expressed in this article are the author/s, and not the position of Intellectual Dose, or iDose (its online publication). This article is republished from LSE Review of Books under a Creative Commons license.