By Ronald W. Pruessen, Emeritus Professor of History, University of Toronto

In 2009, shortly after his inauguration, Barack Obama undertook an intensive policy review to assess the desirability of a military “surge” in Afghanistan.

Vice-President Joe Biden was one of a handful of older advisers repeatedly reminding their new boss to remember the terrible consequences of an earlier generation’s escalation in Indochina. Think very carefully, Biden said at one point, according to Bob Woodward’s recounting, or you’ll be “locked into Vietnam.”

Obama was not dissuaded and committed 30,000 new forces to Afghanistan. Vietnam was “not like this ghost in his head,” recalled Ben Rhodes, Obama’s deputy national security adviser — reflective of the generational divide between the two men noted by James Mann in his book The Obamians.

As president, Biden continues to respect the Vietnam “ghost” — and it hovers over his deliberations and decisions concerning Ukraine.

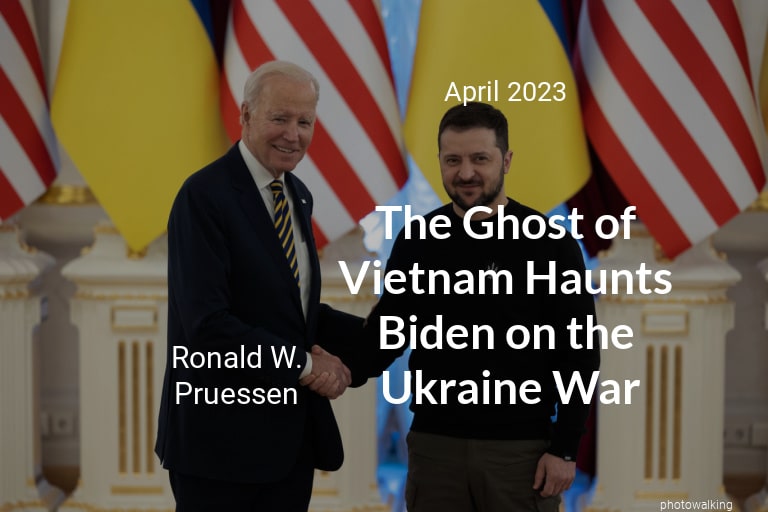

On one hand, Biden is emphatic about support for Ukraine and his passion for stymieing Vladimir Putin’s brutal aggression. In Kyiv in February 2023, the president assured Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy of America’s “unwavering and unflagging commitment to Ukraine’s democracy, sovereignty and territorial integrity.”

These were anything but empty words, given the billions of dollars of aid and military equipment that has flowed to Ukraine — US$27.5 billion to date — the sanctions imposed on Russia and the coalition of powerful allies that Washington has helped to organize who provided another $21 billion in aid.

On the other hand, Biden has kept sturdy guardrails around such words and actions.

Aid with restraint

Massive aid to Ukraine, yes — but restraint that keeps Americans themselves out of harm’s way on land, sea and in the air.

Massive aid, yes — but arm’s length enough to steer clear of a tripwire in the tense relationship with Moscow, especially as a frustrated Putin warns about tactical nuclear weapons.

Recent examples of U.S. restraint include:

- Agreeing to a Dutch plan to provide Ukraine with F-16s but holding back on the pilot training that would have to take place in the United States.

- Agreeing to provide sophisticated Abrams tanks in tandem with Germany’s delivery of Leopard 2s, but avoiding workarounds that could eliminate delays in the actual production of the tanks.

- Avoiding any public discussion of sending American forces directly into the fray.

Lessons learned in Iraq and Afghanistan have obviously shaped the American balancing act in Ukraine, creating greater sensitivity to the problematic gap between desirable goals and prudent methods to achieve them.

Those 21st century experiences highlighted for many the profound costs that can come with overconfident military commitments in distant and difficult terrains.

For someone Biden’s age, however, Vietnam offered a key initial lesson — one that caused him to try mentoring younger leaders in the Obama years, and one that provided weight and momentum to his controversial decision to end the U.S. combat mission in Afghanistan in 2021.

The benefit of Biden’s age

Being an 80-year-old in 2023 means that the lived experience of the Vietnam War adds substantial heft to what others might see as mere ghosts.

Biden was first elected to the U.S. Senate in 1972, surrounded by the storms of protest rising out of war in Southeast Asia. He knew full well how earlier arm’s-length engagement in Vietnam by former presidents evolved into direct embroilment:

Harry Truman’s US$4 billion of support for France’s efforts to defeat Ho Chi Minh (an “outright Commie,” according to Secretary of State Dean Acheson).

Dwight D. Eisenhower’s decision to initiate U.S. involvement using “nation-building” programs, a regional security organization called SEATO and covert operations to repair what he called a “leaky dike” — since it was “sometimes better to put a finger in than to let the whole structure wash away.”

John F. Kennedy’s steps toward deeper engagement to stop the “red tide” — sending 16,000 military “advisers” and allowing Game of Thrones-style machinations that would sanction the assassination of South Vietnamese president Ngo Dinh Diem.Lyndon Johnson’s seduction by what he called “that bitch of a war,” resulting in committing half a million U.S. forces and 58,000 American lives.

- Lyndon Johnson’s seduction by what he called “that bitch of a war,” resulting in committing half a million U.S. forces and 58,000 American lives.

The shadows of such Vietnam ghosts are evident in Biden’s carefully calibrated approach toward Ukraine — especially in his studied resistance to committing U.S. forces to combat.

Avoiding Vietnam’s mistakes?

But the current war is not yet over.

Will the president be able to maintain the balance that has so far allowed him to avoid serious Vietnam-like errors? Will the mature judgment emerging from the 80-year-old’s lived experiences have further staying power?

Problematic past decisions should figure in speculation about what may come next in U.S. support of Ukraine. All the presidents involved in Vietnam had intelligence at least equal to Biden’s.

Each was also capable of both shrewdness and restraint — witness Truman’s firing of wild-eyed Gen. Douglas MacArthur during the Korean War and Kennedy’s handling of the Cuban missile crisis.

At the same time, determination and feistiness — hardly absent in Biden — led these presidents down the road to tragic failure in Vietnam. Just look at Eisenhower’s notion of a viable South Vietnamese nation led by the autocratic Diem, or Johnson’s conviction that awe-inspiring U.S. military power could squash a “damn little pissant country” like Vietnam.

Kennedy was insightful enough to fear the implications of committing even a small number of forces to Vietnam: “It’s like taking a drink. The effect wears off and you have to take another.” He took the first drink anyway.

Johnson then guzzled — even though he wondered if he was acting like a catfish gobbling “a big juicy worm with a right sharp hook in the middle of it.”

Protracted wars create profoundly complex challenges for all leaders. The absence of victory and/or the unpredictable behaviour of enemies lead to military, political, economic and psychological stresses that can undercut pragmatism.

Biden is likely facing a difficult internal struggle. Will the ghosts of Vietnam be vanquished by a new generation of Ukraine-focused anxieties and phantoms?

Ronald W. Pruessen is Emeritus Professor of History at the University of Toronto. He has served as the Munk School of Global Affairs and Public Policy’s Director for International Partnerships & Research and as Chair of the Department of History.

Note: The views expressed in this article belong to the author, and do not reflect the position of Intellectual Dose, or iDose (its online publication). This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license